Laryngeal Paralysis

Back to Fact Sheets

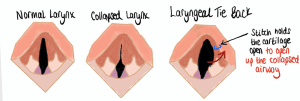

The larynx, or ‘voice box’, is a structure made of cartilage in between the back of the throat and the windpipe (trachea). It is responsible for voice production (phonation), allowing air into the chest when breathing and preventing both food and water from entering the windpipe. While we breathe in (inspiration) the cartilage in the larynx opens to allow more air to go down the windpipe into the lungs.

Download PDF

What is Laryngeal Paralysis?

Laryngeal Paralysis is a condition affecting the nerves of the muscles surrounding the voice box, which are responsible for moving the cartilage at the back of the throat when breathing in. This results in the voice box not moving when breathing because the muscles are paralysed. It can affect one side (unilateral) or both sides (bilateral) and is graded based on its severity.

Causes

There are many causes for this disease. It can be genetic (with commonly affected breeds including Rottweilers, Bull Terriers, Dalmatians, Huskies and Pyrenean Mountain Dogs). Symptoms are usually evident by about one year of age (congenital condition). However, most causes for laryngeal paralysis are acquired and are not due to genetics.

In old dogs, it is most commonly due to degeneration of the nerves and muscles in the larynx. This is a neurological condition called geriatric onset laryngeal paralysis polyneuropathy (GOLPP) which can affect other nerves of other parts of the body too (such as the back legs, or the nerves of the oesophagus – ‘food pipe’).

Laryngeal paralysis can also occur secondarily to some metabolic diseases (such as hypothyroidism), infectious diseases (such as rabies), trauma to the neck resulting in nerve damage (e.g. a bite) or some throat and neck cancers.

Symptoms

Some of the most common symptoms observed include a change in bark (dysphonia), gagging, retching, and coughing (especially when eating and drinking), exercise intolerance, and an abnormal high-pitch noise (stridor), especially when they are panting due to hot weather or stress.

When the disease affects other nerves in other parts of the body, such as the back legs, then the dog may become wobblier on the back legs and struggle to jump into the car or on the sofa. If the nerves of the food pipe are affected then the food pipe can become distended (megaoesophagus) and the dog may regurgitate frequently, having a high risk of some sickness going into the lungs (aspiration pneumonia). Aspiration pneumonia may be mild to very severe, posing a risk to the life of these patients.

It typically takes months to years for symptoms to progress and the back leg weakness or the exercise intolerance can be mistaken for old age or progression of arthritis. More severe signs can include noisier breathing, episodes of laboured breathing (usually while panting due to hot weather), and a blue or purple tongue which usually is observed before patients collapse.

Diagnosis and investigations

Laryngeal paralysis must be diagnosed by assessing the throat (upper airways) whilst an animal is very heavily sedated, usually before anesthetising them (intubation). During throat examination (laryngoscopy) a lack of movement of the cartilage in the larynx can be seen. Full investigation will also often include blood tests to help rule out other diseases and chest x-rays to identify any signs of vomit in the lungs (aspiration pneumonia) or dilated oesophagus (megaoesophagus).

Conservative management

Dogs that are only mildly affected can often be managed with weight loss, reducing stress, exercise restriction and avoiding high temperatures. Harnesses are recommended instead of collars. Symptoms will usually worsen over time as the underlying condition (GOLPP) progresses.

Surgical treatment

Surgery is a palliative procedure recommended in animals with moderate to severe signs. It aims to reduce airway resistance by opening the gap between the laryngeal cartilages. Several techniques can be performed, but a unilateral (one-sided) arytenoid cartilage lateralisation is most commonly performed, also known as a “tie-back”. The paralysed cartilage is tied to the side of the voice box to prevent it from causing obstruction when breathing. Laryngeal function is not restored, but surgery is often very successful at reducing clinical signs and improving quality of life. However, it does not prevent further aggravation of the nerves in the body such as the back legs or the oesophagus.

Complications

10-58% of dogs can develop complications following the surgery. Complications can include coughing, gagging, continued breathing problems and noisy breathing, as well as aspiration pneumonia. The airways are permanently open (more than before surgery) which increases the risk of inhaling food or water while eating or drinking. Despite surgery, there can still be a deterioration in neurological signs (resulting in megaoesophagus and polyneuropathy) post-operatively. The risk of aspiration pneumonia can be reduced by feeding soft, canned food (in the shape of round meatballs) from a height and by offering small amounts of water to reduce the risk of inhaling whilst drinking.

Aspiration pneumonia can also occur months to years after surgery and can affect 8-21% of dogs.

Outcome

Improvement is expected in 90% of dogs undergoing unilateral tie-back. Rest and avoiding any panting is advised for 4 weeks post-operatively. A course of anti-inflammatories and painkillers are dispensed and if required, mild sedatives to aid stress reduction.