Radiotherapy for

Chemodectoma (Heart Based Tumours)

Back to Fact Sheets

Heart Base Tumours

Download PDF

What is chemodectoma?

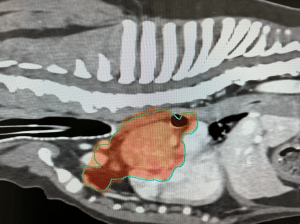

Chemodectoma is a tumour which arises from specialised cells which are found in particular blood vessels in the body (including the aorta), where it exits the heart. Therefore, these tumours tend to arise at the base of the heart (on top of the heart, where all the major vessels enter and exit the heart.

Various symptoms can occur from none at all to life-threatening heart failure. Some dogs present with clinical signs, including exercise intolerance, difficulty breathing, coughing, fainting and/or signs related to blood flow obstruction or pericardial effusion (fluid collecting in the sac around the heart). Pericardial effusion can cause fluid in the belly, fluid around the lungs called pleural effusion and heart failure. Sometimes this can happen without pericardial effusion if the tumour is obstructing certain blood vessels.

Luckily, there are several treatment options available to manage this condition. The treatment recommended for your pet is likely to depend on various factors such as your pet’s age, tumour size, how quickly the tumour is progressing, symptoms, spread (metastasis) of the tumour, compression of the heart, heart function, any blockage of blood vessels and safety of anaesthesia.

Do you ever advise surgery?

Surgery is rarely possible due to the invasive nature of the tumour into blood vessels and the high risks involved.

Pericardectomy (removal of the pericardium which is the thin sac around the heart) is usually strongly recommended if there is pericardial effusion (collection of fluid around the heart). This has been shown to improve outcomes compared to dogs not having this procedure. If a pet is going to receive radiotherapy (RT) and there is no pericardial effusion, then monitoring alone alongside radiotherapy may be reasonable.

It is important to note that pericardectomy only stops the fluid building up around the heart. Whilst this may immediately improve the symptoms, it will not treat the tumour itself, which will continue to grow.

When do you advise radiation therapy (RT)?

Small, incidental tumours without secondary heart compromise: Some chemodectomas are found as incidental findings, meaning they are discovered “by accident” during tests for the other conditions. For example, some are discovered when a cardiologist is performing echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart) to investigate a heart murmur or pre-anaesthesia in an older pet. If the mass is pretty small, not compressing the heart or associated blood vessels or interfering with its function, then “active monitoring” may be recommended. This will involve monitoring the size of the mass and the function of the heart with echocardiography and most likely some periodic checks to check for any spread of the tumour. This is often a very reasonable approach, given the slow growth and progression of many chemodectomas; particularly if the pet is elderly (they may die of old age or another unrelated condition without the tumour causing a problem). If at some point later the tumour becomes problematic or the size is becoming concerning, then treatment may be recommended – ideally before it has caused too many problems (so careful monitoring is required).

Chemodectoma can progress years after initial discovery or successful treatment, so long-term monitoring with regular examinations and imaging studies (e.g. ultrasound and x-ray/CT) is strongly recommended.

Modern-day RT equipment is now very sophisticated and precise, meaning it is far safer to treat tumours like chemodectomas. It is therefore becoming a standard first-line therapy for owners who wish to be more aggressive in the treatment of their pet’s tumour (they feel uncomfortable opting for a “watch and wait” approach), RT can be a useful first-line to try and prevent or delay tumour progression for as long as possible. Different options may be possible, such as fractionated radiation therapy (FRT) or stereotactic radiation therapy (SRT) – see later. It is possible that by treating these tumours earlier when they are smaller will result in better and longer tumour control. But this must be weighed against the potential side effects of treatment, the age of the pet and other health issues (if present).

Incidental tumours with heart compromise and tumours already causing symptoms will be offered treatment, as there is already evidence that the tumour is causing issues (or may be about to), which will get worse without treatment. The tumour may be compressing the heart or great vessels, invading the heart or interfering with blood flow. RT will be offered as the most intensive treatment for these cases (either FRT or SRT, depending on the case). Where owners decline RT, the drug Palladia may be useful in delaying tumour progression and will shrink the tumour in some cases.

Tumours with a high burden of metastasis (tumour spread) tend to be treated with palliative intent, as they have already spread to distant sites such as the liver or lungs or multiple places. These tumours tend to be treated with chemotherapy alone, such as the newer drug toceranib phosphate (Palladia). This can shrink tumours in around 10-25% of cases and in many more patients stabilise the tumour and delay its progression. There are some side effects, but these can usually be well managed with appropriate monitoring and tailoring of the dose to the individual pet.

Chemodectoma tends to progress slowly in many patients, so particularly if there are only a couple of metastases (e.g. one or two small lung nodules or some suspicious lymph nodes in the chest), RT may still form part of the treatment; particularly if a pet is suffering from symptoms relating to the primary tumour or lymph nodes.

Because chemodectoma can progress quite slowly, if tumours only progress in one or two places (e.g. a lung nodule or a liver nodule) and the patient is still medically fit and well, we may even be able to “spot treat” these lesions with a highly focussed type of radiation (stereotactic radiation; SRT). There is some evidence in humans that slowly spreading tumours can be managed well this way.

With treatments such as palliative-intent radiotherapy to manage the primary tumour and drugs like Palladia, some dogs with metastatic chemodectoma can live for many months and in some cases a year or more.

Radiotherapy for Chemodectoma

Radiotherapy is becoming increasingly available and is much more targeted than it was previously, meaning safer and more effective treatments with significantly fewer short and long-term side effects. Recent studies suggest that when radiotherapy is used, the outcome can be very good.

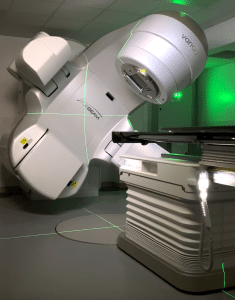

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy; RT) involves treatment with high-energy X-rays, the aim being to kill the tumour. We use a machine called a linear accelerator. Patients lie on the treatment couch and the machine delivers a focussed beam of X-rays from multiple angles 360° around the patient.

Radiation for chemodectoma can be performed with definitive intent (meaning we are trying to give the biggest dose possible to try and get the best outcome) or with palliative intent (lower dose/less frequent radiation treatments to try and improve symptoms whilst avoiding side effects, but without the expectation of long survivals).

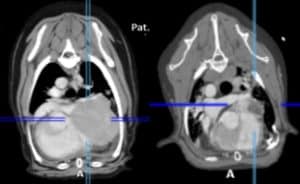

Each radiation treatment is performed under a short, light general anaesthetic. Prior to the start of treatment, a planning CT scan will be needed to help us prepare a bespoke plan for your pet. This helps us to maximise the radiation dose to the tumour whilst sparing the nearby tissues. This will be required even if your pet has had a recent CT scan, as we need patients to be in a very particular and fixed position so that the treatment can be carried out with pinpoint accuracy.

Unfortunately, even with radiotherapy, we usually cannot cure your pet’s tumour. However, radiotherapy can be a very satisfactory treatment for improving quality of life, reducing the risk of side effects and controlling the tumour. RT is well tolerated by most patients; particularly with newer technologies to help avoid side effects and in many cases make treatment courses much shorter.

Does Chemodectoma spread to other places in the body?

Chemodectoma can spread (metastasise) to other sites in the body (such as lymph nodes nearby, lungs, and liver). In particular, the first site of tumour spread is often the lymph nodes inside the chest. Before deciding on the best course of treatment, we need to know the tumour stage. We typically recommend at least a chest (thorax) CT at the time of your pet’s abdominal/pelvis planning CT scan (performed to plan RT). Luckily, extensive tumour spread at the time of initial diagnosis is not common. Specific additional tests may be recommended based on your pet’s individual case.

Will my pet’s tumour-related symptoms improve after RT?

Chemodectoma is sensitive to radiotherapy, though the response can be different for each patient.

The full effect of the treatment may be slow and can take weeks or even months for the tumour to slowly shrink to the smallest size. Some tumour types shrink more slowly and shrink less. In some patients, we might only be able to stop it from growing further. In these patients, the benefit may not be as obvious as there will be less improvement in symptoms.

The hope is that as most tumours at least stop growing, any symptoms will not get any worse (whilst the tumour is under control). Many tumours do shrink with RT, so we hope that the risk of any symptoms relating to the tumour will improve.

In our experience, tumours can shrink by more than half their size in the first 3 months following treatment. The time to maximum tumour shrinkage can be different for every patient.

Radiotherapy Protocols

There are several different types of radiotherapy protocols that we generally offer for dogs with chemodectoma:

- Fractionated Radiation Therapy (FRT; this is the most conventional type of radiotherapy).The total radiation dose is split into multiple small treatments (called fractions) to ensure the radiation is not too damaging for any normal tissues around the tumour in the long term (mainly the heart and lungs). This treatment usually consists of 16-20 fractions, each given once a day (not weekends), over 3-4 weeks. If needed, we can use intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) – a type of RT delivery which means we can significantly avoid radiation dose to the normal structures around the tumour. Because the treatment is delivered in multiple smaller doses, the risk of late effects (see later), particularly to the heart and lungs, is lower. The goal of these types of protocols is to try and achieve the best and longest tumour control possible (i.e. “definitive-intent” therapy)

- Stereotactic Radiation Therapy (SRT). This is a newer type of radiotherapy technique which has come about due to significant technical developments in radiotherapy over the last few years. SRT usually consists of 3-5 treatments delivered once daily over 3-5 consecutive days (Monday to Friday; there are no treatments at weekends). It is a highly focused technique with the goal of treating the tumour but as little surrounding normal tissue as possible. The risk of late side effects is at least the same as with fractionated radiation, if not potentially higher due to the high radiation dose is given with each treatment. Therefore, this technique may not be possible for all tumours – particularly those that are very large, are not well-defined or where there is a lot of fluid surrounding the lungs.

- Palliative radiation therapy – this is where we give a low/modest dose of radiation to try and provide an improvement in symptoms but with relatively short protocols and with little short-term (acute) toxicity. The goal/expectation is not long-term survival but to try and make pets more comfortable for the time they have left. Most protocols are once per day for 5-10 consecutive days, or once per week for 4-6 weeks. Sometimes the choice is based on tumour size/location/type and sometimes is based on owner preference.

- Individual protocols: may be recommended in certain situations, for example, due to a patient’s concurrent medical conditions, owner logistics or pet temperament

Potential side effects related to radiotherapy:

Acute side effects (predictable and temporary)

- Radiation pneumonitis (inflammation of the lung):the lung is very sensitive to RT and even low doses can cause some temporary inflammation. This can occur around 1-4 months after RT is completed and the most typical sign is coughing. Chest X-rays usually show some classic changes, and the symptoms are usually eased with anti-inflammatories. It is rarely a concern as more than enough lung is spared from receiving any radiation at all

- Cough:as the mainstem bronchus (larger airways) are very close to these tumours in many cases, some transient or longer-term cough can be seen in some patients. This is very rarely concerning

- Pericardial effusion:a small amount of fluid collecting around the heart could occur in a few cases, but it is usually not significant. If it occurs, it is typically secondary to the tumour as opposed to RT

- Arrhythmia:it is common for pets to have some alterations in heart rhythm after a course of RT near to the heart. This is very rarely problematic and rarely needs treating. As pets with chemodectomas may already have/develop arrhythmia, it is impossible to know in some cases if the rhythm disturbance is caused by RT or the tumour (or a combination). Whilst extremely rare, arrhythmia could be life-threatening or require specific treatment with medications

- Oesophagitis: inflammation of the oesophagus which could cause some regurgitation and/or retching. This would be unusual in pets with this tumour and is rarely seen

- Death: This is exceptionally rare, but pets can suddenly deteriorate during treatment; e.g. due to anaesthesia complications (e.g. aspiration pneumonia) or other medical conditions

Delayed complications – these are uncommon and typically arise from 3 months after a course of radiation is completed (usually after 6 months or sometimes years after treatment completion). Serious complications such as strictures are rare with FRT.

- Leukotrichia or melanotrichia: white or black hair regrowth/altered skin pigmentation in the radiotherapy treatment site is normal but rare in patients undergoing chest RT

- Heart failure

- Pericarditis causing heart failure or pericardial effusion

- Pulmonary fibrosis causing chronic cough or lung damage which is irreversible

- Rib fracture

- Chronic cough

- Bronchomalacia collapse of the airways causing cough or exercise intolerance

- Oesophageal stenosis narrowing of the oesophagus causing difficulty in swallowing which may require intervention

- Radiation-induced tumours: an exceedingly rare complication (typically seen years after initial treatment) and is usually the development of a tumour arising within the treated site

The goal of radiotherapy is to reduce the risk of serious late side effects as much as possible – we expect <5% overall even years after RT, however in certain individuals the risk may be higher (this will be discussed by your oncologist). The risk may be higher or not fully known, particularly in cases where a relatively novel technique is being used or where SRT is being utilised. However, the risk of severe effects is not high and it is important to note that serious/damaging side effects of RT are rare these days.

Chemotherapy:

Traditional chemotherapy is not very effective for chemodectoma, though it has been used for a long time either as a palliative treatment or after surgery to try and prevent tumour spread. To date, there are no studies proving any real benefit to the administration of chemotherapy to chemodectoma patients as part of first-line treatment. It can, however, show some usefulness as palliative treatment for patients with advanced disease or where other treatments have been used and failed.

Toceranib phosphate (PalladiaÔ) has shown some usefulness in chemodectoma patients and tends to be used where radiotherapy has been declined or was inappropriate/ineffective. We may also recommend it alongside palliative-intent RT or in other individual circumstances.

Palliative Care:

Should you not wish to proceed with any anti-cancer treatment, palliative care should be considered. Palliative care is where we treat the symptoms associated with the tumour without giving any direct anti-cancer treatment. We often recommend anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and/or other symptomatic therapies, but the exact treatment will depend on the symptoms that your pet has.