Radiotherapy for

Nasal Tumours In Dogs

Back to Fact Sheets

Radiation therapy is considered to be the best treatment for Nasal Tumours

Download PDF

Radiotherapy For Nasal Tumours In Dogs

Given the extent and location of nasal tumours, surgery is usually not an option and radiation therapy (radiotherapy or RT) is considered to be the best treatment. Unfortunately, even with radiotherapy, we usually cannot cure your pet’s tumour. However, radiotherapy can be a very satisfactory treatment for improving the quality of life and controlling the tumour. RT is well tolerated by most patients; particularly with newer technologies to help avoid side effects and in many cases make treatment courses much shorter.

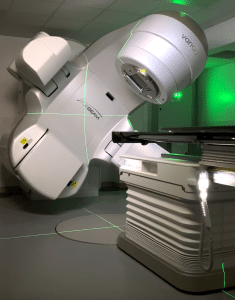

Radiation therapy involves treatment with high-energy X-rays, the aim being to kill the tumour. We use a machine called a linear accelerator, Patients lie on the treatment couch and the machine delivers a focussed beam of X-rays from multiple angles 360° around the patient.

Nasal tumours are sensitive to radiotherapy, though the response can be different for each patient. Overall, studies suggest that at some point after treatment, over 90% of affected pets will have an improvement in their symptoms and/or tumour volume reduction on a follow-up CT scan.

The full effect of the treatment may be slow and can take months for the tumour to slowly shrink to the smallest size. Some tumour types shrink more slowly and shrink less (e.g. sarcomas). In some patients, we might only be able to stop it from growing further.

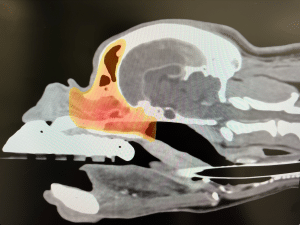

Each radiation treatment is performed under a short, light general anaesthetic. Prior to the start of treatment, a planning CT scan will be needed to help us prepare a bespoke plan for your pet. This helps us to maximise the radiation dose to the tumour whilst sparing the nearby tissues. This will be required even if your pet has had a recent CT scan, as we need patients to be in a very particular and fixed position so that the treatment can be carried out with pinpoint accuracy.

Radiotherapy Protocols

There are several different types of radiotherapy protocols that we generally offer for dogs with nasal tumours:

- Fractionated Radiation Therapy (FRT; this is the most conventional type of radiotherapy).The total radiation dose is split into multiple small treatments (called fractions) to ensure the radiation is not too damaging to any normal tissues around the tumour in the long term. This treatment usually consists of 10-20 fractions, each given once a day (not weekends), over 2-4 weeks. The main acute side effects that can occur include some sore mouth and skin overlying the nasal cavity and sore eye(s) for a couple of weeks after treatment finishes. We almost always use intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): a type of RT delivery which means we can significantly avoid radiation dose to the normal structures around the tumour. This means the degree and severity of acute side effects are massively reduced from what we used to see historically. Because the treatment is delivered in multiple smaller doses, the risk of late effects (see later) is very low. The goal of this protocol is to give the best tumour control possible, and the “average” survival time of dogs with nasal tumours is around 14 months (varies depending on the stage of the tumour as assessed by CT)

- Stereotactic Radiation Therapy (SRT). This is a newer type of radiotherapy technique which has come about due to significant technical developments in radiotherapy over the last few years. SRT usually consists of 3-5 treatments delivered once daily over 3-5 consecutive days (Monday to Friday; there are no treatments at weekends). It is a highly focused technique with the goal of treating the tumour but as little surrounding normal tissue as possible. The risk of acute side effects (see below) associated with this protocol is very low and sore skin, eyes and mouth are unusual and mild if they occur. The risk of late side effects are at least the same as with fractionated radiation, if not a little higher due to the high dose given with each treatment. Therefore, this technique may not be possible for all tumours – particularly those that are very large or involve certain areas of the head. This protocol gives us at least equivalent outcomes to FRT, but some studies have suggested a possibly better outcome (a 2022 study of 129 dogs receiving SRT had average survivals of around 18 months). Either way, the protocol is much more convenient for pets and humans due to significantly fewer treatments and anaesthetics

- Palliative radiation therapy – this is when we give a low/modest dose of radiation to try and provide an improvement in symptoms but with short protocols and with little short-term (acute) toxicity. The goal/expectation is not long-term survival but to try and make pets more comfortable for the time they have left. Most protocols are once per day for 5 consecutive days, or once per week for 4-6 weeks. Sometimes the choice is based on tumour size/location/type and sometimes is based on owner preference

- Individual protocols: may be used in certain situations, for example, due to a patient’s concurrent medical conditions or temperament

Potential side effects related to radiotherapy:

Acute side effects (predictable and temporary)

- Hair loss (alopecia) in the treated site: over the nasal cavity, lips and around the eyes – this can last for many weeks or months and is more obvious in certain breeds (Westies, poodles, Tibetan terriers, other non-moulting breeds)

- Sore skin (radiation dermatitis): sore skin over the nasal cavity/muzzle, around the eyes and end of the nose (nasal planum). There may be hair loss, redness and sometimes oozing, particularly around the eyes and nose. During this time, your pet would need to wear a buster collar, cone, rubber ring or t-shirt to prevent scratching or rubbing of the area, as this could worsen the side effects and delay healing

- Oral mucositis:soreness of the lips and inside lining of the lips, mouth and palate. This may temporarily affect appetite but soft food and pain medications usually prevent this being concerning. May cause some drooling or stringy saliva

- Eye side effects: conjunctivitis, ocular discharge, dry eyes, sore skin around the eyelids or inflamed/swollen eyelids (blepharitis). We can very rarely see damage to the cornea (surface of the eye) resulting in an ulcer. Where an ulcer occurs, it can be vision-threatening, but this is very rare if care instructions are followed. Ocular lubrication gel may be recommended

- Death: This is exceptionally rare, but pets can suddenly deteriorate during treatment; e.g. due to anaesthesia complications (e.g. aspiration pneumonia) or other medical conditions

The risk of these side effects is highest with FRT and usually low or absent with the other two protocols (SRT or palliative RT). These side effects may require symptomatic treatment (e.g. antibiotics, pain relief, anti-inflammatory medication, skin ointment, eye drops) and are expected to resolve within 2-4 weeks after completion of the radiotherapy course. Given the availability of IMRT (as mentioned earlier) these side effects are usually mild and rarely problematic these days. They are short-term, predictable and self-resolving.

Delayed complications – these are uncommon and typically arise 6 months or later (sometimes years) after treatment completion.

- Leukotrichia: white hair regrowth in the radiotherapy treatment site is normal

- Chronic rhinitis: nasal tumours cause a lot of destruction of the normal nasal cavity anatomy and when radiotherapy damage is added to this, it could predispose to periodic inflammation or infection of the nasal cavity, which may require anti-inflammatories or antibiotics

- Cataractsor other changes within the eye such as retinal damage or extra pigment on the eye surface (cornea): this is almost always well tolerated and rarely vision-altering, though mature cataracts causing visual impairment are possible, particularly if a pet survives for many years or after a repeat course of radiation

- Dry eye(keratoconjunctivitis sicca): due to the damage of the tear-producing glands by radiotherapy. This can occur very quickly (e.g. within a couple of weeks of starting radiotherapy) but is usually only temporary – or it could occur later and be permanent (supplementation of teardrops would be necessary life-long in the latter case). It is advisable to monitor tear production (which can be performed at your local vets) regularly after completion of the radiotherapy treatment.

- Fistula:(hole in the hard palate between the mouth and the nasal passage or a hole in the skin over the nasal cavity): rare and usually small/require no treatment. May be more likely in pets that live for many years and/or those that exhibit an exceptionally good response to treatment or receive more than one radiation course over time

- Neurologic changes: seizures, brain damage etc are extremely rare with modern radiotherapy

- Radiation-induced tumours: an exceedingly rare complication (typically seen years after initial treatment) and is usually the development of a bone tumour arising within the treated site

The goal of radiotherapy is to reduce the risk of serious late side effects as much as possible – we aim for <5% overall however in certain individuals the risk may be higher (this will be discussed by your oncologist).

Chemotherapy:

This is usually the least satisfactory treatment for pets with nasal tumours. Multiple conventional injectable drugs have been previously used; however, the success is relatively limited compared with RT.

For nasal carcinomas, the drug toceranib phosphate (Palladia) has shown some efficacy and could be considered in addition to RT in certain situations, or as an alternative to RT where owners feel RT is not appropriate for their pet for whatever reason.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as meloxicam or firocoxib are strongly recommended due to their anti-inflammatory, analgesic (pain relief) and anti-cancer properties (particularly in carcinomas). These are typically recommended alongside radiation or chemotherapy or as a stand-alone palliative treatment.

We are happy to discuss this option with you if you wish to consider chemotherapy for your pet.

Palliative Care:

Should you not wish to proceed with any anti-cancer treatment, palliative care should be considered. Palliative care is where we treat the symptoms associated with the tumour without giving any direct anti-cancer treatment. We often recommend anti-inflammatories and/or painkillers, but the exact treatment will depend on the symptoms that your dog has. The survival time for patients treated with palliative care can range from a couple of weeks up to a few months, depending on the impact of the tumour on their quality of life.